Means "from two different origins" or "created by mixing" or colloquially (sometimes also pejoratively) also mongrel, bastard or blendling. In scientific linguistic usage, this is understood to mean a living being (plant, animal) that has come into being by crossing parents of different breeding lines (genus = genus or species = species). Spontaneous crosses that occur in nature without human intervention are called natural hybrids, especially in the case of plants. In viticulture, hybrids are only the results of crosses between different species or genera. Strictly speaking, however, crosses of the same species are already hybrids (intraspecific = within the species). As a rule, however, only interspecific or intergeneric crosses are understood as hybrids.

- intraspecific = same species of the same genus; e.g. Vitis vinifera x Vitis vinifera

- interspecific = different species of the same genus, e.g. Vitis vinifera x Vitis rupestris

- intergeneric = species of different genera w. e.g. Vitis vinifera x Muscadinia rotundifolia

In plants this does not look nearly as spectacular as in animals and is not immediately recognisable even to experts. This is quite different with hybrids in the animal world, the best known examples being mules (donkey mare x horse stallion), mules (horse mare x donkey stallion) and ligers (male lion x female tiger).

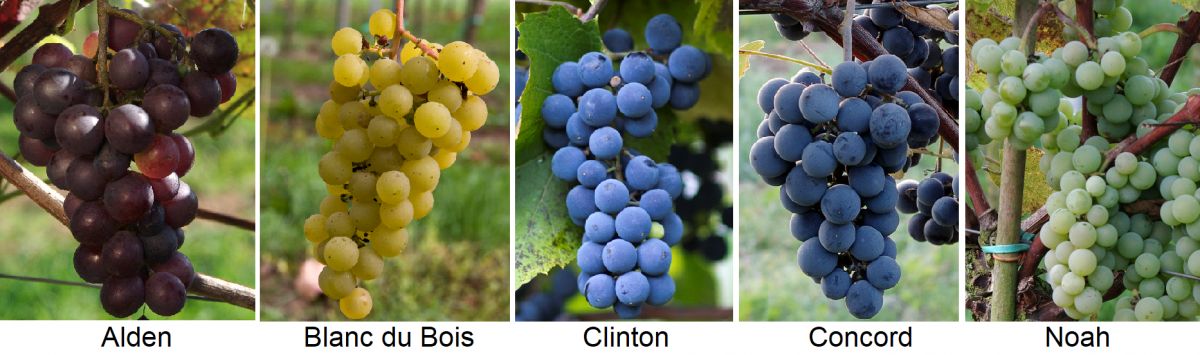

American hybrids

Hybrids in the viticultural sense are crosses between two different species. When they are crossed for the first time, they are called primary hybrids. As a rule, however, hybrids with American genes (e.g. Vitis cinerea, Vitis labrusca, Vitis riparia, etc.) with the desired characteristics are crossed with a European cultivar (Vitis vinifera). The result is then secondary hybrids. Most of the varieties, some of which are resistant to phylloxera and fungus, were created towards the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. Many have the intrusive foxy, which disqualifies them for winemaking, at least in Europe. These varieties created in the USA are called American hybrids, although they also contain European genes. These are Agawam, Albania, Alden, America, Blanc Du Bois, Campbell Early, Cayuga White, Clinton, Concord, Elvira, Delaware, Dutchess, Herbemont, Hopkins, Horizon, Iona, Isabella, Jacquez, Melody, Missouri Riesling, Munson, Niagara White, Norton, Noah, Orlando Seedless, Othello, Rubired, Taylor, Traminette and Vênus.

French hybrids

The partly complex crossbreeding products of the late 19th and early 20th century are called French hybrids, because especially in France, but also in other countries, attempts were made to alleviate the problem of vine decline caused by phylloxera by breeding phylloxera-resistant hybrid varieties for viticulture. Of course, American species had to be used in the process. Valuable help was provided by the US botanist Thomas Volney Munson (1843-1913) with regard to rootstocks, as well as the breeder Hermann Jaeger (1844-1895), who immigrated to Missouri from Switzerland, with regard to American hybrids, which were then used for crossing with European varieties.

There are unequivocal crosses of hybrid varieties with European vines of the species Vitis vinifera or other hybrid varieties (secondary hybrids or multihybrids). Examples include Aurore, Baco Blanc, Baco Noir, Bellandais, Cascade, Chambourcin, Chancellor, Chardonel, Chelois, Colobel, Couderc Noir, De Chaunac, Etoile I, Etoile II, Flot Rouge, Frontenac, Garonnet, Gloire de Seibel, Léon Millot, Lucie Kuhlmann, Maréchal Foch, Maréchal Joffre, Marquis, Neron, Oberlin Noir, Pinard, Plantet, President, Ravat Blanc, Ravat Noir, Rayon d'Or, Roi des Noirs, Rosette, Roucaneuf, Rougeon, Salvador No ire, Siegfriedrebe, Triomphe d'Alsace, Varousset, Verdelet, Vignoles, Vidal Blanc, Villard Noir and Vivarais.

Breeding varieties resistant to phylloxera

When phylloxera was recognised as the cause of vineyard death, attempts were made from the 1880s onwards to breed phylloxera-resistant grape varieties with good wine quality through large-scale crossing programmes. However, the more Vitis vinifera these hybrid varieties had, the better the wine quality became, but all these hybrids with crosses of Vitis vinifera did not show sufficient phylloxera resistance. On the other hand, the phylloxera-resistant hybrid varieties with low or no Vitis vinifera content were often unpalatable (foxy) and unusable for winemaking. Early breeding goals were resistance to the pests of powdery mildew and downy mildew, which were also introduced from America with phylloxera, and other vine enemies, as well as resistance to frost and drought and other quality improvements.

Hybrid breeder

The French breeders François Baco (1865-1947), Albert Seibel (1844-1936), Eugéne Kuhlmann (1858-1932), Jean François Ravat (+1940), Bertille Seyve (1864-1939), Jean-Louis Vidal (1880-1976) and Victor Villard were particularly active in breeding the first and second generation of hybrids. The French hybrids were used as partners for further hybridisations. The US viticultural pioneer Philip Wagner (1904-1996) introduced many to America from the 1940s onwards at his Maryland winery and was largely responsible for their propagation throughout the East Coast. The Wisconsin-born grapevine breeder Elmer Swenson (1913-2004) also used French hybrids for his frost-hardy new varieties. Only relatively slowly did pure Vitis vinifera varieties establish themselves; a pioneer in this respect on his vineyard in the Finger Lakes was Dr. Konstantin Frank (1897-1985), who worked at Cornell University in the US state of New York.

Problem solving through grafting

When breeding new fungus-resistant multihybrids, many of these varieties (especially from Seibel and Seyve-Villard) are still used today as starting material for cross-breeding. The point at which these crosses are no longer considered interspecific because the foreign gene content is "low" is an important point with regard to approval for wines with an indication of origin. However, after countless attempts, the fight against phylloxera was not won by cross-breeding, but by grafting, i.e. grafting European scions onto phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks. Since phylloxera was slow to advance, did not ravage everywhere to the same extent and some hybrid varieties at least produced drinkable wines, many winegrowers ignored the early campaigns for grafting in the first third of the 20th century for reasons of cost.

Bans on hybrids

However, since the high-quality noble varieties of the European grapevine Vitis vinifera could only survive as more costly grafts, strict laws against hybrids were enacted in Germany and Austria-Hungary during this period. According to the state of knowledge at the time, the discussions were very emotional and, from today's perspective, were conducted with absurd arguments. In the book "Die Direktträger" (The Direct Carriers) by Dr. Fritz Zweigelt (1888-1964), published in 1929, it says about this as follows: The specific poisonous effects are a tendency to hallucinations, excesses of anger in men, hysteria in women, mental and physical degenerative phenomena in children. People who regularly drink Noah's wine get a pale, pallid complexion, tremble all over their bodies and waste away. Farmers with refined vineyards, on the other hand, are healthy, hard-working and have numerous children. In France, direct carriers contribute to filling the madhouses.

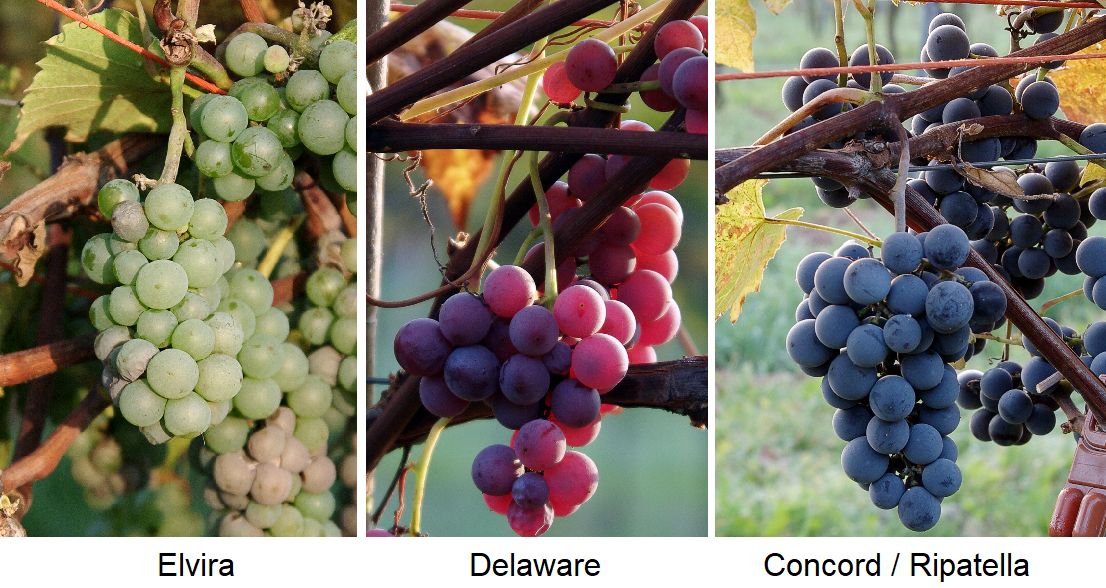

This has put pressure on winegrowers to grub up their American vines and plant grafted vines instead. In many vineyards, however, these low-maintenance, high-yielding varieties survived because they were fungus-resistant and phylloxera-resistant. They were often used as table grapes, as well as for wine jelly, jam and vinegar, but some were also pressed into wine. Many winegrowers therefore refused to grub up their American vines for a long time, so a gradual ban was enforced. In Burgenland in Austria, for example, this affected the Noah grape variety in 1926. In 1929, such wines or blending with them was banned and in 1936 a general ban on planting was decided. Only the production of marc wine for own use was allowed. It was not until 1991 that decriminalisation took place. According to EU regulations, new planting is prohibited, but there are still periods of use for existing vineyards. Examples are the wines Americano (Switzerland), Fragola (Italy) and Uhudler (Austria) with three of the authorised varieties in the picture.

EU regulation concerning hybrids

According to the EU regulation, no wines with an indication of origin may be produced from varieties of interspecific crossings. On the other hand, however, each member state can determine for itself, subject to restrictions, which varieties it wishes to use for this purpose, or which it defines as quality wine grape varieties. Strictly speaking, all crossings with American or Asian vines would be excluded. However, this caused some problems with new breeding, because under the term PIWI (fungus resistant), an important breeding goal is to achieve the highest possible resistance to fungi such as botrytis and both types of powdery mildew, other pests or environmental conditions such as frost. However, this requires Asian/American species, as many of the Vitis vinifera varieties usually do not have sufficient resistance.

Because of the Regent variety, there was a dispute between Germany and the EU in this regard. The question was whether Regent should be considered a hybrid. Due to its American Vitis labrusca genes, it has a high content of the anthocyanin malvidin-3,5-diglucoside (200 to 300 mg/l). This substance, called "hybrid dye", does not affect health or taste, but its presence proves American genes and is set at a maximum of 15 mg/l content in a quality wine on the recommendation of the INAO. The designation "hybrid" or "direct carrier dye" is misleading, however, because non-crossbred and/or grafted Labrusca vines also possess the dye.

Quality study

The prohibition of interspecific crossings for wines with an indication of origin (quality wines, country wines) has always been mainly justified by the EU with a lack of wine quality. In order to provide an objective basis for decision-making in this respect, a study was carried out by external contractors from Germany, France and Hungary on behalf of the European Commission in 2003. The research and scientific data were collected at INRA and Geisenheim. The study was to provide answers to the following three questions: 1) Are there quality differences between wines made from Vitis Vinifera varieties and wines made from interspecific varieties? 2) Is it possible to reduce the use of plant protection products in viticulture by using interspecific grape varieties? 3) What would be the economic impact of using interspecific grape varieties?

For the study, 18 interspecific grape varieties or wines made from them were included. The varieties Baco Blanc, Baco Noir, Bianca, Chardonel, Couderc Noir, Medina (1), Seyval Blanc, Traminette, Vidal Blanc, Villard Blanc, Villard Noir and Zala Gyöngye were divided into the three groups "Old interspecific varieties", "Central European interspecific varieties" and "New mildew resistant interspecific varieties developed outside EU". The four new German varieties Johanniter, Merzling, Regent and Rondo also contain a small amount of foreign American and Asian genes, but were combined as a fourth group as reference varieties with "Fungus tolerant Vitis-vinifera varieties". This is due to backcrossing of the initial results with the Vitis-vinifera varieties involved. The Regent variety was mentioned as "not considered as interspecific" and considered to belong to the Vitis vinifera species, although it also has genes foreign to the species.

In terms of wine quality, the study found that both poor and good quality are achievable, provided that the interspecific grape varieties are appropriately cultivated in terms of their growing practices and planted in appropriate areas. Concerning the impact on the environment, the results were very positive. The use of pesticides would be considerably reduced if interspecific varieties were used. They are considered to be particularly suitable for organic viticulture. Considering the impact on the market balance, the study estimates that an increased use of interspecific varieties would cause an increase in production of about 1.8% in the EU within the next ten years and thus the economic impact is negligible.

In the final analysis, the authors of the study suggest that the current ban on the use of interspecific grape varieties should be maintained in order to provide an incentive for such research, which would lead to new and better interspecific varieties. However, the study was received differently in the individual member states and vividly illustrates the problems within the European Union of creating uniform rules accepted by all for 27 countries and more. Denmark, England, the Netherlands and Sweden are in favour of lifting the ban. Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, on the other hand, are in favour of keeping it. The countries Germany, France, Luxembourg and Austria, on the other hand, welcome the study and the objective in principle, but see the research work only at the beginning. See also under grapevine systematics and a list of grapevine-relevant keywords under grapevine.

Animals: By Алексей Шилин - own work, public domain, link

Grapevine varieties: Ursula Brühl, Doris Schneider, Julius Kühn-Institut (JKI)

Voices of our members

Using the encyclopaedia is not only time-saving, but also extremely convenient. What's more, the information is always up to date.

Markus J. Eser

Weinakademiker und Herausgeber „Der Weinkalender“