Such incidents of prohibited or even harmful wine manipulation date back to ancient times. Attempts are made to "improve" quality through unauthorised additives or to feign a false identity through manipulations such as fraudulent labelling or blending with inferior wines, circumventing wine regulations. The most spectacular and extensive wine counterfeits of modern times are described below:

Artificial wine scandal Italy 1968

In the 1960s, Italian wines became popular, particularly in Germany, due to Italy becoming a popular holiday destination at the time, and millions of hectolitres were imported. These included the cheapest products of alleged brands such as Chianti (in the kitschy, bast-wrapped demijohns), Lambrusco and Valpolicella, which had never seen the growing regions concerned. Many were enriched with sugar and water, embellished with bovine blood and the plant mucilage agar agar (made from algae) and the fiery lustre was created by adding plaster. Over 200 wine adulterators were reported, some of whom had also used river water and the broth of spoilt figs or bananas to sweeten the wine. The wine law introduced in 1963 with the DOC system had clearly not yet taken effect.

Glycol scandal Austria 1985

In a 2010 interview with Josef Pleil, the long-term president of the Austrian Winegrowers' Association, he explained the background to the 1985 glycol scandal (heavily abridged): The roots for the wine scandal probably lie in the early 1970s. In order to prevent the exodus of many small farmers, every winegrower from the border region was authorised to plant an additional 0.5 hectares per farm. This was intended to prevent the many small farmers from entering the Viennese labour market. After just five years, this resulted in an expansion of around 15,000 hectares of vineyards and thus overproduction. At the beginning of the 1980s, however, wine consumption declined throughout Europe.

In Germany at that time, there was good demand for sweet wines. Some "resourceful specialists" tried to meet this demand by adding diethylene glycol to simple, cheap table wines to simulate high-quality Prädikat wines and offering them at very low prices. This worked quite well at first.

First suspicion

In December 1984, an unknown man with a German accent turned up at the Federal Agricultural and Chemical Institute in Vienna, placed a bottle containing a syrupy liquid on the table and remarked: "This is what the Austrian wine counterfeiting scene uses". It was the diethylene glycol used in antifreeze. After mass production in the 1970s and the fall in the price of Austrian quality wines, the state winery inspectors had long had a vague suspicion. So much Prädikat wine could not be produced naturally. But applications to search the premises of suspected wine merchants were regularly rejected by the court as disproportionate.

Use of diethylene glycol

Of course, there were already analytical quality samples for wines back then, but the detection limit at the time was 200 mg diethylene glycol per litre of wine. However, this was well known in the wine counterfeiting scene. In order to reduce the glycol content to below the laboratory detection limit, it was mixed one to ten with unadulterated wine. As a result of the information described above, laboratory methods were refined in Austria, and now glycol wine could be recognised as adulterated from as little as 5 mg/l using the gas chromatography method. When word of this got around in the counterfeiting scene, sewage treatment plants collapsed because the glycolic wine was poured into the sewer in extreme quantities that are still unknown today, just to avoid being convicted or caught. Hundreds of thousands of hectolitres of wine had to be distilled into industrial alcohol.

Table wine became Prädikat wine

The majority was produced by winegrowers from Lower Austria and Burgenland, some of whom were also advised by a chemist. Diethylene glycol was added to give the wine more "body and sweetness ", which was particularly appreciated by consumers in Germany at the time. Glycol was not only used to turn ordinary table wine into Prädikat wine, but also to produce thousands of hectolitres of artificial wine. These liquids looked and tasted like wine, but had never come into contact with grapes or wine.

Water was simply mixed with tartaric acid, malic acid, potash, glycerine, staghorn salt and diethylene glycol, among other things. The agent is not harmless. The limit is 16 g/l, which can even be fatal. This amount was detected in an ice wine from Burgenland. However, due to the mostly low concentration, there were hardly any health problems. The most common side effects were nausea and kidney problems. There were no serious illnesses or deaths.

House searches at winegrowers

The ball finally started rolling when a winegrower wanted to claim conspicuously large quantities of antifreeze for tax purposes, even though he only owned a small tractor. The targeted inspections began at the beginning of April 1985. Diethylene glycol was detected in 34 of 38 samples taken at the first winery inspected in Apetlon, and a similar picture emerged at a second winery in Podersdorf. Finally, on 23 April 1985, the Ministry of Agriculture sounded the alarm and warned against glycol wines. A total of 55 detectives carried out 850 house searches at winegrowers, traders and chemical companies. A total of 80 suspects were arrested in July 1985 and February 1986. Around 23 million litres of wine were confiscated, but the total volume of counterfeit wines could never be clarified. According to the investigations, at least 340 tonnes of diethylene glycol had been added to the wines since 1976.

Spread to Germany

The scandal eventually spread beyond Austria's borders, as the majority of the adulterated wines were delivered to Germany, where some of them were "further treated". Large German wine bottlers from the federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate illegally adulterated German wine with Austrian glycol wine. The Pieroth company in particular was targeted by the investigating authorities. However, the company denied having any knowledge of the offences. Sensational reports in West German newspapers led to a negative climax. The Bild newspaper of 12 July 1985 ran the headline "Antifreeze wine at grandma's birthday party - 11 poisoned".

This sparked a media campaign against Austrian and especially Burgenland wines, which eventually found its way throughout Europe and overseas. Even the "New York Times" featured the scandal on its front page. The BATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives) ordered all wines from Austria to be withdrawn from circulation.

Criminal proceedings

After lengthy investigations, there were 325 complaints, 52 criminal charges for offences against the Food and Wine Act and 21 charges of commercial fraud. It emerged from the criminal proceedings that the first "applications" in Austria had presumably already taken place on a smaller scale from the 1976 vintage onwards. The 1980 to 1984 vintages were particularly affected because, according to witnesses, the wine merchants involved "became increasingly greedy". This was done with great criminal energy and sophistication.

The tankers for export had been manipulated in such a way that the tap intended for taking samples led to a small container of around 200 litres, which contained unadulterated wine. During the trials, which lasted for years, some of those convicted received up to eight years in prison. One of them committed suicide. Large wine merchants went bankrupt, even if they were not directly involved, and large wine producers had to file for bankruptcy.

Damage to image

The damage to Austria's image was considerable and brought the country's wine industry to the brink of ruin. In the USA, the FBI prevented the ÖVP politician Alois Mock (1934-2017) from presenting Austrian wine as a gift during a visit by President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004). Austria's wine exports fell by 95% overnight. At the end of 1986, ÖWM was founded to help alleviate the consequences of the scandal through marketing measures. However, the incident ultimately had a very positive effect. At the end of August 1985, the National Council passed the new wine law, which was described as the "strictest wine law in the world". Among other things, every bottle had to be labelled with a band (replaced by a round label on the cap in 2008) to prevent misuse.

New wine law

This led to a conflict between the governing parties SPÖ, FPÖ and ÖVP. The wine industry, dominated by the ÖVP, opposed the hectare yield restriction and the banderole and only wanted to agree to this if wine taxation was reduced. However, Federal Chancellor Fred Sinowatz did not give in to the demands and so the wine law was passed in August 1985 against the votes of the ÖVP. This came into force on 1 November 1985 in stages, but had to undergo several amendments in the following years, as many points could not be implemented.

Methanol scandal in Italy 1985/1986

The 1970s saw a wine boom in Italy. Mass-produced wines were made in huge quantities, particularly from the red wine variety Barbera, which is suitable for mass production. In 1985 and 1986, the so-called "methanol scandal" was publicised, which affected many Barbera wines due to the large quantities involved. These included the DOC wines Barbera d'Asti, Barbera del Monferrato and Piemonte del Barbera. The cheap and extremely toxic alcohol methanol was added to the wines to increase the alcohol content. Above a certain level, this leads to blindness and, in extreme cases, death. There were hundreds of sick people and eight deaths. The main supplier of this swill was a wholesaler from Manduria near Taranto in Apulia. As a result, these wines were almost unsaleable and stocks were almost halved.

Château Lafite-Rothschild counterfeit Hong Kong 2002

Counterfeit Bordeaux wines often come from China. It is estimated that around nine times more high-class Bordeaux wine is sold there than is produced in France. A hotel in the southern metropolis of Guangzhou sold 40,000 bottles of Château Lafite-Rothschild every year. However, the winery only supplies around 50,000 bottles a year to the whole of China. Around 300,000 bottles are to be marketed there each year. This means that more than eight out of ten bottles are counterfeit. The process is relatively simple. A cheap wine from Bordeaux is filled into a bottle similar to the Châteu Lafite-Rothschild and sealed with a cork from a great vintage bearing the Lafite brand. Finally, a fake label is applied, which is easy to produce with today's means (scanning the original and changing the vintage). If necessary, original bottles with original labels are used, as the business with such expensive top-quality products is very lucrative even for smaller quantities.

At the beginning of 2002, it was discovered that in Hong Kong, medium-priced red wines from Bordeaux were being transformed into a Château Lafite-Rothschild 1982 vintage, an extremely expensive wine of the century rated at 100 points, using counterfeit labels and capsules. The bottles were worth around €25 and then fetched up to 25 times the price as "Chateau Lafite-Rothschild 1982" - i.e. €625 per bottle. However, the business is on the wane because the government has launched a campaign against corruption, waste and luxury. Xi Jinping, who has been General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party since 2012, wanted to restore some credibility to his country.

Brunellopoli scandal in Italy in 2008

A second scandal, known as "Brunellopoli" or "Brunellogate" (derived from "Watergate") in the Anglo-American press, occurred in Italy in 2008. Several companies, including the well-known wineries Antinori, Argiano, Banfi and Frescobaldi, were suspected of food counterfeiting. The public prosecutor's office confiscated several million bottles of DOCG Brunello di Montalcino from the 2003 vintage, which was highly publicised at the Vinitaly wine fair.

The specific accusation was that instead of the exclusively authorised Brunello variety (a Sangiovese clone), the Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon varieties from the south had also been added. In May 2008, the responsible US import authority decided to ban imports of Brunello. This ultimately led to a change in the production specifications. Many winegrowers, including Angelo Gaja, proposed relaxing the rules and no longer having to produce the wine from 100% Brunello-Sangiovese in order to make it more competitive. In the end, however, the strict rules remained in place. The 6.5 million litres of Brunello and 0.7 million litres of Rosso di Montalcino that were confiscated had to be marketed as DOC or IGT. Hardly any wine counterfeiting could be proven and only a few people were convicted.

Methanol scandal Czech Republic 2012 with 50 deaths

In 2012, around 500 bottles of vodka, rum and fruit brandy with counterfeit labels were seized during a raid in Zlin in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic. A high methanol content was detected in the samples found. There were numerous deaths in the following years, although the number of unreported cases can be assumed. It is estimated that up to 50 people died and a further 50 suffered serious health problems.

China labelling fraud 2013

The Viennese winery Mayer am Pfarrplatz exports wines to China and has visibly made a name for itself with its products. In 2013, counterfeit products with a special label appeared there. The name of the winery was copied, but instead of the picture of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven on the original label (because he had lived for a time in the house on Pfarrplatz, which is now known as the Beethoven House), it included a picture of Johann Strauss. It can be deduced that the latter is much better known in China and therefore more effective in advertising.

Wine scandal in Italy 2019

In July 2019, police raided a total of 62 wineries and homes in the regions of Abruzzo, Puglia, Campania and Lazio on suspicion of wine counterfeiting, must enrichment and illegal oenological techniques. The public prosecutor ordered the seizure of four wine companies and 30 million litres of suspected adulterated wine. The accusations: Cheap Spanish wine was sold as Italian DOC and IGT quality at dumping prices. Must was illegally enriched with sugar and other illegal additives in order to increase the production volume. Heavily flawed wine is also said to have been embellished using illegal cellar techniques. In addition, an employee of the central Italian unit for food control and fraud prevention was accused of informing the companies concerned about the internal affairs of the authority and upcoming inspections.

More wine counterfeiting

Further spectacular cases involving extensive wine counterfeiting of very old vintages from Bordeaux and Burgundy are described in detail in separate keywords. The German wine rarity collector Hardy Rodenstock (1941-2018) could never be proven to have had fraudulent intent. This was certainly the case with the Indonesian-born wine merchant Rudy Kurniawan, who was sentenced to ten years in prison for fraud. In this incident, the US billionaire and wine rarity collector William Koch (*1940) was (once again) the injured party.

Further information

General information with historical background information and current wine law issues can be found under the keyword wine adulteration. For more information on this topic, see Wine law and lists of relevant keywords under the keywords alcoholic beverages and alcohol consumption.

Source Glycol scandal: The wine scandal, Walter Brüders, Verlag Denkmayr, ISBN 3901838457

Source Pleil interview: Wiener Zeitung 19.7.2010

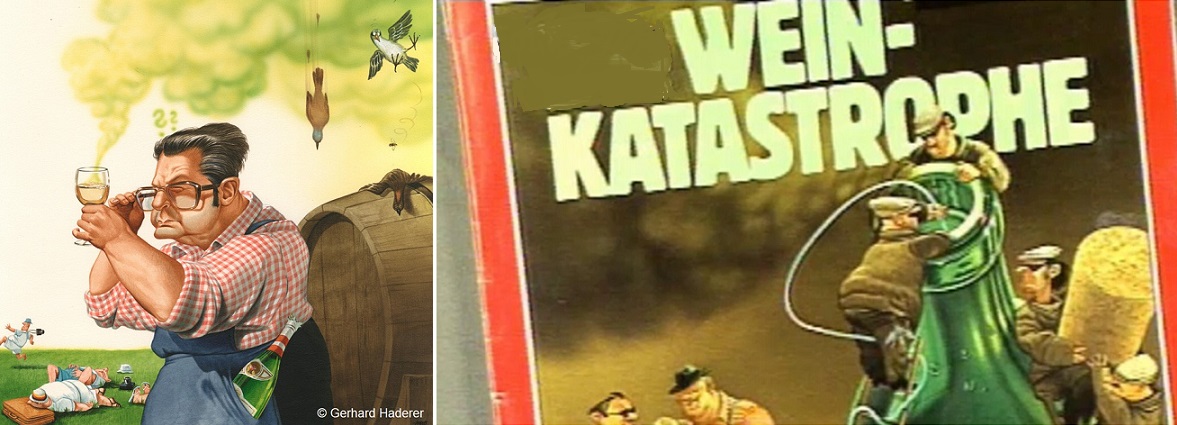

Cartoon on the left: Gerhard Haderer

Cartoon on the right: Profil

Voices of our members

For my many years of work as an editor with a wine and culinary focus, I always like to inform myself about special questions at Wine lexicon. Spontaneous reading and following links often leads to exciting discoveries in the wide world of wine.

Dr. Christa Hanten

Fachjournalistin, Lektorin und Verkosterin, Wien